The other week, I went to see Wes Anderson’s new movie, The French Dispatch. If you haven’t seen it yet, I recommend it. Some reviews argue that it leans too heavily into Anderson’s trademark stylization, losing sight of what ought to be the key goal: telling a human story. This is understandable—it’s a sort of collection of short stories and vignettes rather than some clear, overarching narrative. But I think the critics are wrong.

I’m not here to write a review of the movie, but in the last few minutes of it, the purpose of all those stories about expatriate American writers in France becomes clear. Life is a messy, complicated thing, and everyone’s got their own character, their own lens, and their own version of the story. It’s an homage, in a way, to the art of writing, the power of the pen or typewriter to give form to a past which no longer exists but for the stories we tell of it. And the stories that get written down last the longest.

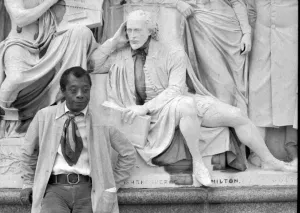

I’m talking about The French Dispatch, because it inspired this piece: a contemplation of the thoughts of one such American expat writer in France: James Baldwin. That final message of the film isn’t so different from what I ended up learning again from Baldwin—how many times we can learn it, I don’t think there’s a limit—that life is messy and that no one story can explain everything, because human beings just aren’t that way.

Almost as if in testimony to life’s complexities, Baldwin was famously difficult to categorize—and I would hardly blame you if you didn’t know a lot about him, as his time was an era of giants like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X, among so many others. He is known most often as an incredibly perceptive writer of social commentary, primarily in the 1950s and 1960s, but he started writing as a critic of films and books. In his career, he wrote novels, essays, plays, and poetry. Before all that, barely a teenager, he was a preacher in Harlem, where he grew up. He was an American, but he lived most of his adult life in France. He was a Black man and a gay man. James Baldwin, after all these complicating details, was James Baldwin, despite attempts by the FBI, among others, to categorize him as merely a Black writer or a gay writer or an expat or a Black expat.

Of course, Baldwin did write about race and racism in America, and it’s that subject, in light of Anderson’s film and Baldwin’s complex identity, that I mean to discuss. I hope, in reflecting on him, his writing, and this issue, to communicate to the reader some of his profound insights.

Today, discussions of racism in “our republic,” as Baldwin liked to say, often end up as discussions of “critical race theory” (CRT). CRT is, at best, barely understood by most people. At worst, and quite commonly, it’s profoundly misunderstood. Put simply, it’s a theory that racism in America is systemic, that biases against the success and equality of non-white Americans are self-perpetuating. In other words, the theory claims, even if there were not a single personally racist white American in the country, non-white Americans—particularly Black, brown, and Native Americans—would not achieve success proportional to white Americans. This extends, too, to our legal and criminal law enforcement system, focusing more on and handing harsher sentences down to Black and other non-white Americans.

It’s a theory I personally find convincing. After all, it’s quite hard to make the case that social and economic advantages and disadvantages aren’t, to some degree, inherited by way of institutions that are built to perpetuate them. With such a long history of marginalization and exclusion of non-white Americans in this country, it only makes sense that unequal outcomes would persist, to no fault of the disadvantaged. Consider, for example, our legal system: if you are a judge or jury-member, you don’t have to have hatred in your heart for people with darker skin than you to have your unconscious psyche shaped by that same long history to irrationally see threats—and, by extension, guilt—in some and not in others. And there’s little doubt that American policing was a large part of that history of oppression and continues to operate, in the most generous view as if on a sort of path dependence, in perpetuation of injustice.

Conservatives have been keen to rail against CRT. The standard claims are that it is fundamentally anti-American and that it teaches hate. Former President Donald Trump called it an “ideological poison.” Representative Madison Cawthorn dubbed it a “divisive cancer.” Senator Ted Cruz claimed it “says America is irredeemably racist,” and described it as “every bit as racist as the klansmen in white sheets.” Josh Hawley rejects it and said he places his faith in “the goodness of the American people.”

Progressive organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People claim it recognizes “that racism is more than the result of individual bias and prejudice. It is embedded in laws, policies and institutions that uphold and reproduce racial inequalities.”

The debate—or, perhaps, fight—over CRT has, without a doubt, become a critical component of political campaigns and rhetoric. This theory, a sort of stand-in for talk simply of racism, is, in a sense, a touchstone of our current zeitgeist. And that’s not all that surprising, given how long racism has been another touchstone.

One of the key examples often cited not precisely of CRT but of the sort of public commentary inspired by it is the 1619 Project of the New York Times and Nikole Hannah-Jones. In her introductory essay of the project, Hannah-Jones presents a story of American history that challenges traditional versions. It’s titled, “Our democracy’s founding ideals were false when they were written. Black Americans have fought to make them true.”

Her story begins with an assertion (or a hypothetical—it’s not clear) that the true founding date of the United States could be considered the year 1619 rather than 1776. This was the year the first African people, abducted from their homelands, were brought to America to be sold to colonists as slave laborers. Hannah-Jones claims that the founders, evidenced by their ownership of human beings, never believed the famous, lofty words of the Declaration and Constitution. Instead, she tells a story in which Black Americans did believe in those ideals, and it was by their fight for those ideals that they have been realized at all.

I think, for the most part, it’s a version of American history which rings quite true. The importance and influence of Black Americans in fighting for the fuller realization of our founding principles is hard to overstate. But I do struggle with its outlook and certain claims. It’s not hard to see why conservatives claim CRT is anti-American if one of the most prominent public intellectuals in support of it declares the country’s founding ideals false. And the article, especially as a reflection of CRT’s core tenet of racism’s systemic character, seems to suffer from some dissonance. On the one hand, the discrimination of politics and its outcomes are systemic or impersonal. On the other hand, it is the individual actions of Black Americans which have torn it down over time. I think this confusion is of principal importance, and it’s something that Baldwin responds to with great clarity in his writing.

There is no doubt that Baldwin would sympathize with Hannah-Jones’s desire to be critical of America. And to those who might claim such criticism is anti-American, Baldwin’s view is insightful. As he says, “I love America more than any other country, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” It’s a feeling I certainly share.

He wrote extensively on the importance of critical study of our history in particular, because, “Appearances to the contrary, no one in America escapes its effects, and everyone in America bears some responsibility for it.” In other words, “We cannot escape our origins, however hard we try, those origins which contain the key—could we but find it—to all that we later become.”

However, after stating his love of country and justifying his criticism, Baldwin continues,

“I think all theories are suspect, that the finest principles may have to be modified, or may even be pulverized by the demands of life, and that one must find, therefore, one’s own moral center and move through the world hoping that this center will guide one aright.”

It is this view which is, I think, core to Baldwin’s insights about race and racism in America, particularly in light of CRT.

Baldwin doesn’t explain his suspicion of “theories” in this passage, which is the preface to the 1984 edition of his first collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son. But in the essays contained therein, one may begin to see his philosophy about life unfold with each word and paragraph and essay.

The hints of it can be seen in his comments about how most people talk about race in America. For one example, he writes,

“The story of the Negro in America is the story of America—or, more precisely, it is the story of Americans...He is a social and not a personal or a human problem; to think of him is to think of statistics, slums, rapes, injustices, remote violence; it is to be confronted with an endless cataloguing of losses, gains, skirmishes; it is to feel virtuous, outraged, helpless.”

Importantly here, Baldwin has stated that this is the story of Americans, rather than America. He criticizes views taken of race in America which resort to a catalogue of facts, figures, and statistics: appeals to or reliance on data to quantify and explain a human struggle as something “social.”

Throughout his writing, Baldwin seems to place a heavy emphasis on the importance of individual morality: that we choose how we walk through life, how we interact and respond to others. Confronted with the death of his father, the birth of his half-sibling, and the aftermath of a race riot in Harlem in the same week, Baldwin seems to have a reckoning of sorts with life and the world.

He is reminded of a Bible passage from his childhood, which ends, “as for me and my house, we will serve the Lord.” For Baldwin, it was a moment in which he realized that “nothing is ever escaped.” Seeing the destruction wrought by racism and inequality in his home, he describes being filled with anger and hate. But, he writes,

“I knew that it was folly, as my father would have said, this bitterness was folly. It was necessary to hold onto the things that mattered. The dead man mattered, the new life mattered; Blackness and whiteness did not matter; to believe that they did was to acquiesce in one’s own destruction. Hatred, which could destroy so much, never failed to destroy the man who hated and this was an immutable law.

“It began to seem that one would have to hold in the mind forever two ideas which seemed to be in opposition. The first idea was acceptance, the acceptance, totally without rancor, of life as it is, and men as they are: in the light of this idea, it goes without saying that injustices is a commonplace. But this did not mean that one could be complacent, for the second idea was of equal power: that one must never, in one’s own life, accept these injustices as commonplace but must fight them with all one’s strength. The fight begins, however, in the heart and it now had been laid to my charge to keep my heart free of hatred and despair.”

Baldwin relates a similar feeling when he details how, fueled by hatred of American racism, he was nearly driven to murder someone, saying, “I saw nothing very clearly but I did see this: that my life, my real life, was in danger, and not from anything other people might fo but from the hatred I carried in my own heart.”

For Baldwin, the struggle with American racism was akin to a moral battle. It was a plague of American society which not only decimated equality and opportunity. Though it sought to destroy the dignity of Black Americans, it was most effective in crushing the humanity of the racist, annulling his human dignity by his seeking to annul others’. “Our dehumanization of the Negro then is indivisible from our dehumanization of ourselves: the loss of our own identity is the price we pay for our annulment of his.”

Baldwin may have agreed with CRT insofar as he was critical of the “liberal dream” of color-blindness as a solution to racism. But it’s clear that Baldwin’s view is that American racism is a personal and moral problem requiring personal and moral conquering, rather than something which might be explained or solved by the “social sciences.”

It’s a view regarded by many today, I suppose, as old-fashioned. Today, the explanations and responses to racism that are in vogue are founded on systemic, structural explanations of society. As much as many figures on the American political right, like Josh Hawley or Ted Cruz, are indeed intellectual charlatans, there is a grain of accuracy in their claim that CRT may be traced to Marxism. Marx viewed history and society in this way, that everything could be explained by some overarching theory of impersonal economic forces, like those which Baldwin finds suspect.

And it’s fair, I think, to say that Baldwin’s answer leaves us wanting. We want there to be some society- or politics-level solution to racism, and so we are inclined to believe it is fundamentally a society- or politics-level problem. But what he recognizes, I think rightly, is that such explanations and solutions forget humanity in a way. Our institutions are the way they are because of human actions, and they can be made to be other ways by human decisions.

As citizens—something Baldwin seems to have taken very seriously with his frequent description of America as “this republic”—we must retain a belief in the value of individual agency, the importance of individual actions. If we lose that—as we are likely to, if we rely on simplistic, systemic theories and solutions of our society’s failings—then democracy loses its value and purpose.

In the end, Baldwin’s life and writing seem to vindicate that lesson suggested by The French Dispatch, a movie about writers in some way or another like him, that life is messy. It can’t be easily explained, and the stories we settle on—to explain ourselves, our nation, our failings, or our nation’s—are merely the versions that won out from so many writers jostling over the typewriter. Just as those theories are really the products of individuals, so are the phenomena they try to explain. It’s up to us to take life seriously and to try as best we can to bear the moral burden of life and do right by others. In Baldwin’s immortal words,

“Our humanity is our burden, our life; we need not battle for it; we need only to do what is infinitely more difficult—that is, accept it.”Subscribe to Spectacles

Comments

Join the conversation